Super DIRT Week is here. True, the World of Outlaws are a Tuscarora Mountain range away. Yes, the Moody Mile at Syracuse went six feet under six years ago. But the spirit remains. Venues change, but campgrounds and entry lists stay fat. In the modified stock car universe, Super DIRT Week is still the harvest to a season of planting. When I was 11 years old, it was Christmas, Halloween and Thanksgiving rolled into one.

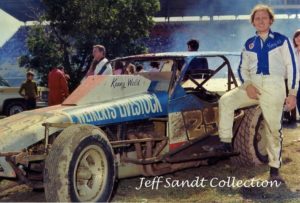

The 1974 Schaefer 100 at Syracuse was our first real road trip. Father began the four-hour drive at 4 a.m. We arrived at the New York State Fairgrounds to find Kenny Weld holding the new track record. In the 100-miler, he hit pit road too hot and broke the rear suspension. Weld’s famed rival Jan Opperman ran all day in Joey Lawrence’s Mustang. Rain arrived after Lap 95. Under caution, leader Billy Osmun pointed to the sky. Merv Treichler seethed.

Rain and Syracuse became synonymous. It helped in 1975 when the Labor Day race was postponed to precede 239 time trials. Dad exited early because Oswego Speedway had extended its season for visitors like him. “The Steel Palace” felt like Yankee Stadium from the smell of methanol and Hofmann hot dogs to the vibrations and noise of unlimited supermodified machines. The idea of Oswego hosting Super DIRT Week since 2016 could not have been imagined.

Dad opted for Oswego over Weedsport where KARS sanctioned Garry Gollub’s biggest win. Sunday saw Jack Gunn’s guys stage the mile’s first winged sprint laps. Bobby Allen averaged 106 MPH. Weld’s original Gremlin pitted twice yet Osmun shadowed Dick Tobias at the end. On our way home, dad found one diner open. We were surprised to find Toby’s triumphant Davey Brown Mustang II. Two decades later when the Moody Mile fell silent, it was the Zemco 410 by Brown which powered Billy Pauch’s eternal standard of 144.59 MPH.

We got to Syracuse earlier in 1976. Bob Eckert’s brother George was entrenched alongside the Leon Harrison Pinto on which he crewed by Friday when we headed up I-81. We had never camped with rowdy racers. They laughed all night. I was too young to recognize the role of alcohol, but the booze helped explain why Tom Hager thought he was “Evel Knievel” at 3 a.m. As penance, Hager had to go 100 miles on a broken ankle.

For decades, the biggest race at Syracuse was the USAC Championship date during the state fair. Once that was modified, Champ Cars shifted to Fourth of July until attendance dipped. Why not add it to Super DIRT Week? Bob bought tickets for us then watched outside. Fans hoped to see Opperman, but Jan was in an Indy hospital. Lee Osborne led but Pancho Carter won. Off to Oswego we went. Supers were paired with modifieds that enabled Richie Evans and winner Maynard Troyer to warm our frozen forms. Next day on the mile, Evans raced a Weld Gremlin after Bentley Warren’s Oswego winner eclipsed 112 MPH.

Syracuse felt the sting of Chinese craftsman Grant King, who came to Indy in 1963 from Portland, OR. King built roadsters for A.J. Watson and rear engine rockets that won Dover and Milwaukee for Andy Granatelli and Art Pollard. Grant then built the safest and fastest USAC sprint, midget and champ cars. Ken Brenn asked him to “clean up” a Gremlin for Syracuse. King countered that a new car would be easier but to make it profitable, King needed a second customer. Brenn found fellow New Jersey construction magnet Tony Ferraiuolo, who hired Gary Balough away from the original Weld car. A. Ferraiuolo & Sons won the 1976 Schaefer 100 with timed fuel injection and 535 cubic inches. Both were then banned.

Super DIRT Week 1977 was a muddy mess. Hay bales tripled in price. Modifieds broke the beam but never raced. The whole thing got shoved back two weeks then six months. Sun did shine on USAC when the Salt City 100 became Larry Dickson’s only “Big Car” victory. Dad did not purchase tickets so we circled. Outside turn four came the hellish sound of steel on concrete as Jim Hurtubise wrecked Tim Delrose’s champ car. Mail-order minister Opperman qualified a Will Cagle Gremlin then hosted Sunday services in a cold mist.

Balough and Ferraiuolo won twice in 1978, topping 100 miles in spring then adding a third straight Schaefer 100 by autumn. April proved too soon because winter on Lake Ontario was not done. The Moody Mile ripped apart. A dozen cars crashed together on its narrow back chute. Tighe Scott cleaned the cage off above Wayne Reutimann’s helmet.

After three Fourth of July experiments, Glenn Donnelly created the Syracuse Super Nationals in 1978. To level the playing field between Williams Grove and Oswego, wings were outlawed for this World of Outlaws point race. Independence Day winners Kramer Williamson, Weld and Paul Pitzer had been challenged by no supers but without wings, supers more than kept pace. Hometown boys Bob Stelter and Jack Tobin qualified quickest and Bentley bagged the first leg. Inverted for another 32 miles, a Buck Buckley sprint car earned $3500 handled by Jim Edwards of Van Nuys, CA. Those were the headlines. To those of us in attendance, there was relief. Randy Wolfe flipped for 200 yards. Van May clipped a super, tumbled through turn one, reached for the roll cage to pull himself free, and found none. Wings were added as an act of mercy and no super ever again threatened to win. We tailed Bentley and Stelter to another Oswego double in which George Kent outran Evans before Jim Shampine’s offset 8-Ball etched new records on four consecutive laps that peaked at 103.78 MPH.

Father was weary. After seven trips in five years, Bob could no longer justify his expense with the scarcity of wheel-to-wheel action. We stayed away in 1979 when Jack Johnson won for New York and 1980 when Weld and Balough changed the game again. Politics played a part in our absence because father followed Lindy Vicari from Reading to East Windsor and Nazareth. Vicari hated Donnelly. Glenn was green when Lindy helped him through early Syracuse promotions, but too wise to let Vicari steal his lease on NYS. No, if I wanted to see Syracuse again, it had to happen without dad.

It was a Camaro full of friends who hauled me to the 1981 Syracuse Super Nationals. In his first look at the joint, Doug Wolfgang cruised 63 miles for $15k. The Wolf likened the mile to a frozen lake but admitted that his Howells Four “felt like a Cadillac on a cloverleaf.” Oswego was outvoted for a string of saloons. Weld inspired Troyer to expand into DIRT and caused Treichler to add ram-air induction that defeated Lou Blaney.

Few races boasted as much talent as Syracuse Super Nationals but so many stars seemed all dressed up with no place to race. Rolling Wheels Raceway changed the parade when rain delayed the World of Outlaws to Super DIRT Week 1982. Bruce Ellis and I arrived with the rain. I was soon over budget, sleeping in a stable after catching the NYS-to-Oswego bus to catch Kent and Doug Heveron handling business. On the mile, Sammy Swindell and Treichler took top honors in 1982.

Vicari opposed Super DIRT Week 1983 at Nazareth National, where four Eckerts on payroll pushed it into bankruptcy within a year. I returned to Syracuse in 1984 when Swindell brothers Sammy and Jeff finished first and second. For the first time, I left town before the modified race, opting for Selinsgrove’s dramatic Jack Gunn Memorial victory by Steve Kinser over Wolfgang and Williamson. Skipping Syracuse in 1985, I consumed a Friday slice of Super DIRT Week 1986 when Guy Smith and I spent the day on the mile and night at RWR for 320 modifieds. I had slapped a Speedway Scene decal on Kinser’s nose wing and was able to describe the honor to Steve’s brother Randy Kinser a day later in Lawrenceburg, IN. It became a badge of honor to go to great lengths for a Syracuse alternative.

The 1987 World of Outlaws tour included me on 83 of 96 nights. I was Rich Bubak’s sole crewman for a month before locating a real mechanic. Bubak had been on the Indy Mile but was unprepared for NYS abrasion. After three hot laps, four tires were baby smooth. Frontstretch wind buckled Bill Peri’s wing supports. He almost flipped backward into Bubak, who lifted and lost the last transfer spot. Syracuse separated supers into their own race won by Gene Lee Gibson in 1987. Sammy set a world record but surrendered to Blaney after 31 of 35 miles. Oswego VIP status extended to Rich and Fred Rahmer. Next day, we watched Jimmy Horton win his first Syracuse 200 before embarking on 3,000 miles to Ted Johnson’s next race in San Jose, CA.

Seven years passed until I returned to Super DIRT Week; far from my Indianapolis home until business in New England brought me through New York in 1994. I drove a Buick Skylark to Syracuse for Billy Pauch’s nail biting defeat of Blaney. So pleased was Pauch by his first Outlaw success that he skipped Rolling Wheels where Jeff Swindell swept the regular race and one postponed by four months. Blaney then chased Horton’s second Syracuse 200 wreath while I sat in Seekonk, Mass.

Winged midgets at Seekonk were again chosen over Syracuse modifieds as John Gibson’s 1995 passenger. Our quest to earn a living from this crazy sport pulled us to West Springfield, MA. Trackside publisher Dean Nardi sketched a newsletter that became Flat Out Illustrated but Nardi had nothing for Gibson, who was bitter only four months when Ted Johnson made him the only announcer The Outlaws have ever known.

When we left Syracuse for Seekonk, neither Johnson nor Donnelly had hinted at the 1995 Super Nationals being the final one. Glenn replaced Outlaws with 360 match races, street stocks and USAC Silver Crown curtain calls. One of those 2003 Champ Cars was driven by current Outlaw race director Mike Hess.

Atmosphere is always difficult to describe. Super DIRT Week was like the Knoxville Nationals cut its temperature in half, spread itself across the entire Iowa State Fairgrounds, ran engines for five days, raced nearby every night, partied around the clock and woke to 100 MPH practice powered by coffee, hot dogs and beer. The post-midnight focus was “The Ghetto” that grew from concert speakers on a flatbed to its very own souvenir shop. An enormous bonfire made it like “Burning Man” for racers.

In the flicker of flame, I was spotted by Alex Friesen, a thorn in Donnelly’s side by offering Big Money from Ransomville to Williams Grove and Grandview. Only one year later, Alex passed away after a snowmobile accident. His nephew Stewart eventually won four of the final six Syracuse 200 epics. Oswego is a fine place for a party. Ask any Canadian at the International Classic, the atmosphere lives on.