Leland Vance May was as wild as the wind across El Paso, Texas. He left there in 1971 in a Corvette convertible towing a yellow Number 13 sprint car complete with chrome cage, Peace sign and photographer’s vest of Acapulco Gold. Van headed for Hanover, PA. He simply followed big brotherly advice from Walter “Dub” May, who had tested Central Pennsylvania as suggested by Bobby Allen. A man could earn a living on Fridays at Williams Grove, Saturdays at Lincoln, and Sundays at tracks from Hagerstown to Reading to Susquehanna. Central PA was the World of Outlaws of its day. In four trying seasons, Van won only once albeit at The Grove. Over the next 13 seasons however, May amassed 70 popular victories topped by the 1977 National Open. He also won in midgets and one 358 modified stock. Wins were only part of Van’s appeal. At the track, he was his own boss with a gallows humor and razor wit for one who sustained several concussions. Van May stepped clear of some smoldering catastrophes. He left one roll cage in turn one at the Syracuse mile. His crash during the 1985 Tuscarora 50 tore an air conditioner from its tower, prompted Port Royal to better elevate its flagman, and earned Van a helicopter ride. In short order, he was winning again. Nothing could stop the whirling dynamo. He seemed indestructible. A rock shattered his eyeglasses at the 1979 Eldora Nationals, slicing his cornea. Yet he rebounded with his only 12-win season. Ben Cook’s personal buggy with Gaerte Engines was Van’s best ride. It netted 10k from the Ohio Speed Week final in Zanesville and second against Outlaws at Lincoln and Lebanon Valley. When asked if he ever beat The Outlaws, Van will say, “Yes, but not all on the same night.” Cook 33 was the fastest package of the 1985 Knoxville Nationals only to get wiped out on the start. Soon after returning to the ‘87 Nationals for Swofford Electric of Texas, another rock damaged his other eye at Selinsgrove and ended May’s career. Far from bitter, he attended virtually every race of 2019 at Williams Grove, Lincoln, Susquehanna or Grandview. He is humbled that so many remember him so fondly. Van May Night at The Grove sold out of T-shirts in an hour. A second batch at Lincoln vanished almost as fast but not before he saved one for his 1984 Open Wheel Magazine biographer. Autographing it, Van smirked at me and said, “Now remember, this will only be valuable when I’m dead.”

Tulsa, Oklahoma’s Terry Doss drove 100-inch supermodifieds on Fridays at his hometown fairground and Saturdays at State Fair Speedway in OKC. NCRA sanctioned the touring series in which Doss scored second at Dewey in 1976 then first in Enid in ‘77. Terry took this 1978 Gary Stanton-built sprint car to Granite City and Knoxville, where he was ninth in his second try. Rookie to the 1979 Western World in Phoenix, he reached eighth against the 1980 World of Outlaws at Oklahoma City. One week before Nationals, he finished second at Knoxville then fifth on his preliminary night. It was the following summer’s final wingless Nationals of 1981 when Terry’s terrible crash threw debris that disabled one fan for the rest of her difficult life. Doss dragged 100-inch and 86-inch wheelbases to a fourth Knoxville Nationals in 1983 then spent two seasons winning in Tulsa before Terry retired in 1986.

Hatfield, Pennsylvania’s Paul Lotier was a quick study. When he moved from 318 cubic inches to 467 modified stock cars in 1980, he won right away. Two years later in just his third trip to Williams Grove with a big block sprint car “Low Tier” parked on the homestretch. Prior to sprints, Paul honed his craft on Fridays at Big Diamond, Saturdays at Grandview, and Sundays at Penn National where Debbie Tobias inherited promotership after her father became a USAC fatality. Lotier won the 1980 Freedom 76 centerpiece to Grandview’s season and scored on successive Super DIRT Weeks at Fulton and Brewerton. After he and Debbie married, Lotier became a bit of a test pilot for Tobias Speed Equipment that soon distributed Gamblers to devote full production to the Tobias Taxi breadwinner. Paul pursued DIRT road shows to French Canada, where “La-Tee-A” crossed sixth at the Autodrome Drummond. In the big shindig at Syracuse, he finished fourth with 320 and fifth at 467ci. So dominant was the skinny Gremlin he assembled for Steve Reho (eight wins in 14 Penn programs) that sarcastic losers printed “St. Paulie’s Speedway: Run What I Brung” T-shirts. Tired of tape measures and cries of nepotism, Paul turned to sprint cars and advised Fred Rahmer to do likewise. Lotier had a little taste of wings when “Run What You Brung” hit modifieds for real. In his very first Outlaw event, Lotier landed fifth at The Grove. In his first sprint race at Lebanon Valley, he qualified fastest. Eight years later, second-place at that Valley near Massachusetts marked the high point of Paul’s time with the World of Outlaws. He was a 1986 Port Royal winner with 410 sprint and 358 modified. Love brought more family pain after The Port dealt Scott Tobias a career-ending shot to the head. Lotier soldiered on as 1987 Port champion in the Walter Dyer 461. They were the last winners ever at the Florida State Fair. Lotier crossed sixth at the Kings Royal of 1990. Two weeks after earning Rookie of the Year at Knoxville Nationals, Paul crashed out of the 1991 Sharon Nationals. He impacted a fence post that broke his seat and spine. Paul Lotier never walked or raced again. Paul Lotier III did race three-quarter midgets before fielding a USAC Eastern sprint car and the midget “SpeedSTR” conceived by Richie Tobias.

El Paso, Texas touched the World of Outlaws again with this car built by Tony Diaz for owner/driver Ted Lee, president of a trash collection service. Ted had some talent. He won at Firebird in 1984 and Manzanita in 1985, opened 1986 with Outlaws in California then dominated at home until eighth at Eagle and Fargo. Lee locked into finals of Knoxville Nationals and Gold Cup on prelim night. At the end of that 1986 season, Jac Haudenschild was hired. Jac won at Devil’s Bowl and Lee agreed to field Wesmar Challengers on a full pull. They started strong by winning the first Mini Gold Cup (Ted was Top Nine) then won nothing other than one night in Denver when Steve Kinser was disqualified for refusing engine inspection. Still they split fourth-place money in 1987 points. One summer later when Jac needed a friend in a hurry, Lee sent a car to Houston that Haudenschild raced through Nationals. Ted dominated the El Paso Speedway Park that he came to help operate. EPSP died, diverting business to Southern New Mexico Speedway until SNMS died, diverting business to Vado Raceway Park.

Simi Valley, California’s Dale Laakso had descendants from Finland. More important to Dale’s desire to race sprint cars were his descendants of the Cerwin-Vega audio empire. Green as grass, he was a raw rookie to the final Ascot Park CRA season of 1990. Laakso had scarcely learned how to back into corners when he tried wings at the 1991 Outlaw opener in El Centro. Four months later, Dale drove to New York with The Outlaws. He favored a big stage as evidenced by four sporadic starts of 1992 at Knoxville Nationals, Gold Cup, National Open and Syracuse. He hit a couple TV telecasts from Manzanita then quit after the 1994 U.S Dirt Nationals at Terre Haute. Any improvement was infinitesimal. Laakso went on to shift Acura gears on street corners by 2003 when coincidentally Cerwin-Vega filed bankruptcy. Music purists can still score a pair of their elite speakers because Cerwin-Vega was absorbed by the Gibson Guitar Company of Memphis, TN.

Sedro Woolley, Washington’s Steve Beitler took an odd road to the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame. As a driver, Steve’s skills were slightly above average. As a promoter however, he has few peers. Beitler first left his Pacific Northwest corner in 1989 when the USA club offered fat cash to independents like Beitler and Rich Bubak. Steve spent five years with the World of Outlaws without a Top Five but reached sixth-place at San Jose, Bakersfield, Fargo and Oklahoma City. Beitler bought the Bubak shack in Knoxville to cut three slices of its unparalleled point funds. Extra laps helped him crack his second Nationals final in 1995. He came home to sell sprint car components until an opportunity arose to purchase Skagit Speedway in 2001. This caused an unfortunate rivalry with Steve’s mentor Fred Brownfield, who had promoted Skagit until he was shoved south to Grays Harbor where Fred died in 2006. Beitler added that oval in Elma to his promotional sphere in 2014. He paid 40k to Jonathan Allard at the 40th Dirt Cup then agonized over turning that 410 destination into a remote stop on the ASCS National 360 series. As a child, Steve wanted to race cars, fight fires, and play that rock and roll. He achieved all three. His grasp of the Big Picture courted free press to the point of hauling me around. I toted 240 cassette tapes of which Alice Cooper’s Greatest Hits became Beitler’s favorite. He especially liked to arrive with “No More Mr. Nice Guy” playing especially loud.

Garry Rush, the most accomplished racer in the history of Australia, was 49 years old — “long in the tooth” according to one countryman — when this final U.S tour stretched to Georgia. He had toured America for eight straight summers. Rush won in West Sacramento then scored second in its 1974 Gold Cup. He made the Pacific Coast final at Ascot Park. Garry was a 1975 Calistoga NARC winner with Ken Woodruff. Rush ran the Gold Cup and 1976 Western World for Mike McCreary. He performed at Pacific Coast and 1977 Western with Ed Watson. He ran the 1978 Nationals for Jerry Smith and Western with Gary Stanton, who was handed enough U.S currency to build a 1979 model in which Garry won its Manzanita debut and scored seventh at Eldora, third in Kansas City, and seventh at Nationals. He teamed with Bob Trostle to clock a Knox County record then drove Fred Kain’s car at 1980 Nationals. Gambler Chassis Company provided a 1985 Knoxville Nationals mount that hit Top 12 in all five features. He set up a 1991 U.S tour for Garry Rush Jr. Down Under, he was instrumental in the creation of Parramatta City Raceway. Rush conquered PCR as driver, car owner to Donny Schatz and Joey Saldana, and as track owner/operator. In 1988, Garry sold “Sydney Speedway” to David Lander, who bankrolled that 1993 U.S tour. Brian Healey brought 410 engines and World of Outlaws to Australia before he died in 2009. Rush was again prompted to own a piece of “Valvoline Raceway” that he sold to Barry Waldron in 2014. Garry Rush remains the only seven-time winner of the Grand Annual Classic in Warrnambool, Victoria.

One of the strongest rivals to Garry Rush was Steve Brazier, son of stock car steering Stan, father to Garry (21 years old above) and granddad to 2020 jockey Jordyn Brazier. Highway tragedy claimed Steve Jr. Steven even toured NorCal before importing a 1977 Charlie Lloyd chassis to Australia from Central PA. His boy became Bob Trostle’s 18-year old rookie to Knoxville Nationals. Steve shipped a car for Garry to wheel around Knoxville for all of 1992. They notched a second to Danny Lasoski then won in Farmington, MO. After winning his first Grand Annual Classic, Brazier began a second season at Knoxville for Mike VanderEcken but left to do Dirt Cup and NARC Speed Week for Ted Finkenbinder. Back in dad’s car for Nationals, they made an eastern swing through Selinsgrove and Tuscarora 50 then decided to headquarter in Hanover just like Dub and Van May did 23 years before. Garry won at Lincoln, went to Nationals then returned to drive the vaunted Weikert Livestock 29. He opened the Outlaw campaign as 1997 Mopar pilot of Gary Stanton but departed to sub for injured Brian Paulus. In dad’s device, Garry finished first at Williams Grove, seventh at Kings Royal, and first in the final race of Knoxville’s 1997 season. He opened another Outlaw season with Stanton but left Mopar after Mississippi. Since son and father were feuding, Steve hired Danny Smith before welcoming Garry back to crack Nationals grid and Dakota circles at Fargo, Grand Forks and Sioux Falls worth 10k. He returned to Port Royal for sixth-place in Central PA’s famous Dyer Masonry 461. Steve Brazier liked machines massaged by Karl Kinser so he bought one such ‘85 Gambler and another 2001 Maxim that won 50 Grand at PCR. They added another 50k from Sydney in 2006 during a rare cameo. Steve Brazier decided that he and Garry would basically only race in December and January because only Americans made worthy adversaries.

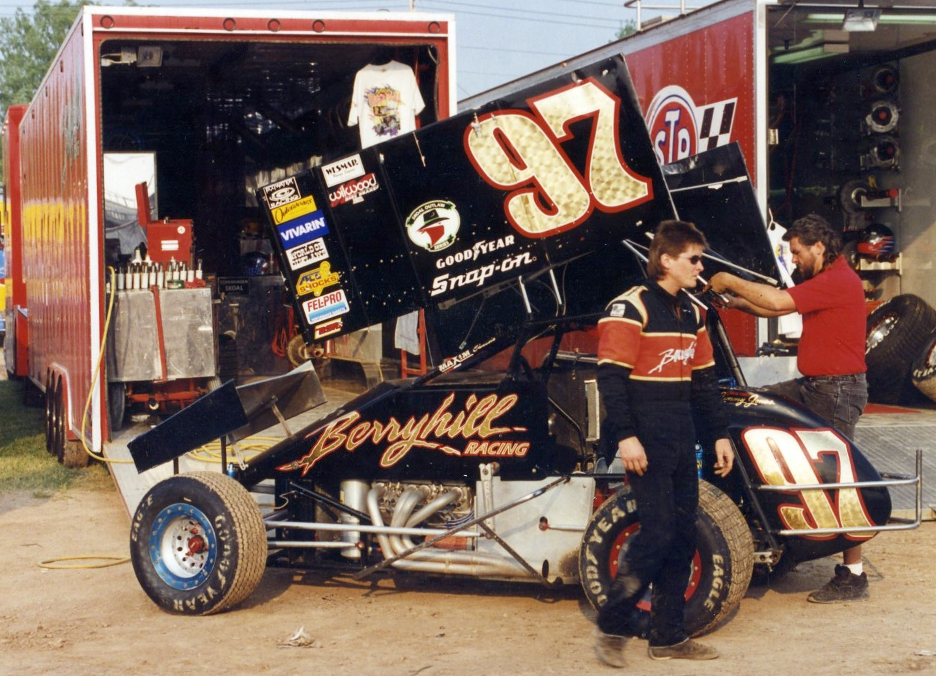

Broken Arrow, Oklahoma’s Aaron Berryhill was the 1992 World of Outlaws rookie of the year. Auto racing had known Aaron’s family since 1987 when Bob Berryhill’s Chili Bowl company sponsored a local midget race. Bob sold that snack line to Keebler for a couple million that helped fund the racing dreams of Aaron and big brother Adrian, both of whom began in midgets then strapped on eight cylinders. Aaron entered 22 Outlaw events without losing rookie status. Highlights of his freshman campaign were Knoxville Nationals final and sixth in the Devil’s Bowl that improved to fourth in spring. Outlaw experience helped defeat NCRA at Joplin and OKC before a solid sixth at ‘94 Nationals. Third at Houston’s Battleground Speedway would be Berryhill’s career-best with the World of Outlaws. Three months later at Knoxville, methanol cooked his legs. He missed four months. Painkillers were easy to find. Crew chief Jimmy Jones first toured with 1984 Outlaw rookie Greg Wooley of OKC then studied under Karl Kinser, the wizard who taught Jones how to fuel a 410 Chevrolet. Jimmy and Aaron shattered the Tri-State track record, beat NCRA at Wichita, and reeled off three straight Tulsa triumphs to open 1997. Courtney Grandstaff chose Aaron to follow Mike Peters as Trop Artic explorer of 1999-2000. They beat NCRA from Mandan, ND and Arlington, MN to Mayetta, KS. Court chased NCRA to Central PA until replacing Berryhill with Australia’s Brooke Tatnell. Jones took Jerrod Wilson and Sean Walden to the 2001 NCRA trail. At the end of 2002, Aaron drove Sean’s car and struck a deal with Mike Walden for an NCRA effort that topped Tulsa in 2003. Aaron and Adrian built a check cashing business that soon siphoned funds into the NASCAR aspirations of Adrian’s boy Tanner. Aaron was a divorced father trying to raise his daughter. His second wife was Brandye Rife, stepdaughter to Steve Smith. Stevie Smith ironically married Lance’s sister Kendra Blevins of Broken Arrow. Neither union lasted longer than a Wesmar engine. Jones returned to Indiana to help Justin Marvel then bonded so well with Robert Ballou that Ballou listened to no one else. Back home, Jimmy helped Tulsa’s Dustin Morgan. Berryhill’s last Outlaw start was the 2006 final in Las Vegas. He beat ASCS at Lake Ozark in 2008. “The Family Stone” was a 2005 movie that featured Rachel McAdams in black T-shirt depicting driverless Trop Artic 66. It was certainly no display of affection for Aaron no matter what story he might float.

Columbus, Ohio’s Sarah Marie Fisher was the fastest woman in closed course history. Fisher’s family was a veritable think tank. Her mother Reba taught school and flew airplanes. Sarah’s father Dave and his brothers George and Charlie all impacted the World of Outlaws and auto racing as a whole. Charlie served as Gambler test pilot who regularly reduced one-lap records around Eldora and Chillicothe with experimental hoods, wings and nitro-soaked air filters. He formed Fisher Racing Engines that earned Outlaw wins with Craig Dollansky among others. George Fisher ceased driving to field cars that carried Dale Blaney to All Star excellence until George died of cancer in 2016. A fourth Fisher was a fluent guitar player until his early death. Dave Fisher was a steady winner before devoting Saturdays to his daughter. Dave had Sarah in a quarter midget by five and karts by age eight. She fired off her first sprint car at 15. Fisher finished sixth against Georgia All Stars, second at Pittsburgh during Western PA Speed Week, tried ‘97-98 Knoxville Nationals, and was second at Eldora in the 1998 All Star final. “The Road to Indy” was a slogan linking NAMARS Midgets to the new Indy Racing League. Dave Fisher took it literally. He bought a Hawk by Mike Streicher and longer Dan Drinan roadster. Neither turned a wheel on dirt because the “Road to Indy” was paved. Daddy and daughter won five midget races in 1999 (none with USAC) that showcased Winchester’s demand for high speed finesse. Fisher was a National Honor Student enrolled at The Ohio State University when IRL afforded rookie status to the 2000 Indianapolis 500. Second in the Miami Grand Prix of 2001 was the best Indy Car finish ever by a woman until Danica Patrick’s win in Japan. Sarah broke her back in the 2001 Indy 500. She received the rare honor of hot lapping a McLaren during some 2002 U.S Grand Prix pageantry. She formed her own team in 2008 with husband Andy O’Gara. They have two children. Chili Bowl 2015 ended her 16-year absence from midget racing. Sarah Fisher would co-author a book titled “99 Things Women Wish They Knew Before Getting Behind the Wheel of Their Dream Job.”